What is spasticity?

Spasticity is the uncontrolled overactivity of muscles caused by disrupted signals from the brain. It is common in persons with more severe traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). People with spasticity may feel as if their muscles have tightened and will not relax or stretch. They may also feel muscle weakness, loss of fine motor control (for example, being unable to pick up small objects), and notice overactive reflexes or clonus (when certain joints move in a rhythmic, but uncontrolled way).

What you need to know

- Many people with TBI either do not have spasticity or have easily controlled spasticity.

- Your brain injury may cause the muscles in your body to become stiff, overactive, and difficult to stretch. The muscle may “spasm” or tighten suddenly. This is called spasticity.

- Spasticity may not be bothersome and does not always need treatment.

- Spasticity may come and go. It may be worse during certain activities, or it may become worse at night. It can interfere with sleep or limit the ability to function. When problems such as these arise, you may need to consider treating the spasticity.

- Severe spasticity may cause almost continuous spasms and can cause permanent shortening of muscles, making even simple movements difficult

- There are ways to treat spasticity or relax muscles, ranging from controlling triggers (discussed below) to taking medicines. Medications are more commonly used when several muscles are spastic.

- When only a few muscles are affected, focal treatments such as nerve blocks and botulinum toxin injections (described below) may be considered. There may also be surgery options.

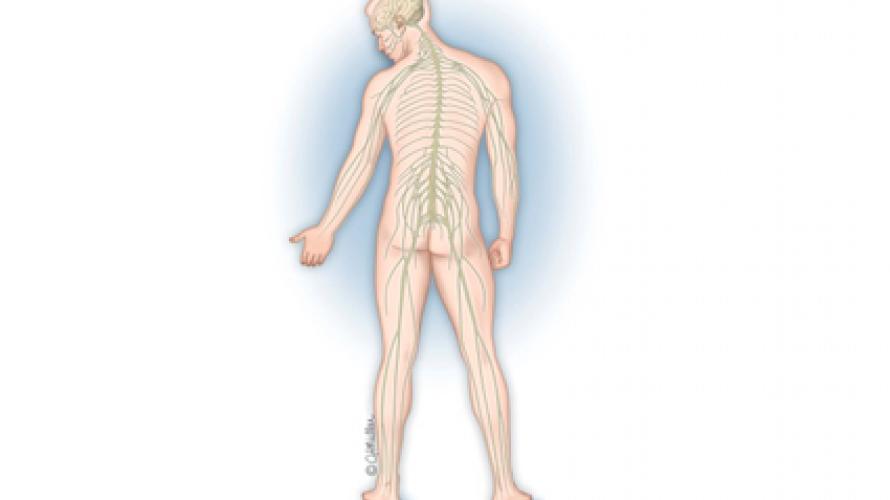

Understanding Your Body: How Muscles Work

Your brain communicates though your spinal cord and nerves to your muscles and causes them to contract and relax. If the signals that control relaxation are lost, then overactivity, or spasticity, may occur.

What are the symptoms of spasticity?

The symptoms and degree of spasticity are different for each person and can include:

- Sudden, involuntary tightening or relaxing of a limb, or jerking of muscles in the trunk (chest, back, and abdomen).

- Hyperactive (overactive) reflexes, such as a muscle spasm when the arm or leg is lightly touched.

- Stiff or tight muscles at rest, so that it is difficult to relax or stretch. This is more pronounced than normal muscle stiffness that may happen when a person sits for a long period of time. Muscle tightness during activity can make it difficult to control movement.

When am I most likely to experience symptoms?

Spasticity can happen at any time but is most likely to occur when you:

- Stretch or move an arm or a leg.

- Have a urinary tract infection or a full bladder.

- Have constipation or large hemorrhoids.

- Have pain or injury to the arm or leg.

- Feel emotional stress.

- Have any kind of skin irritation.*

(*Skin irritation includes rubbing, chafing, a rash, in-grown toenails, or a skin sensation that is too hot, too cold, or causes pain. This also includes pressure sores, or ulcers, caused by staying in one position for too long).

Does spasticity need to be treated?

Spasticity is not always harmful or bothersome and does not always need to be treated. Sometimes, however, there are problems caused by spasticity that can be bothersome or harmful including:

- Pain when muscles tighten.

- Stiffness and loss of motion. Depending on the muscles and limbs involved, this may affect:

- Walking/balance, use of arms and hands for dressing, eating, and other activities.

- Difficulty taking deep breaths.

- Poor positioning in a chair, wheelchair, or bed.

- Poor sleep and tiredness during the day.

- Pressure ulcers on the skin.

- Difficulty bathing or using the toilet.

What can I do to manage my muscle spasticity?

Spasticity is usually managed with a combination of physical treatments, medications, focal Interventions, and sometimes infusions of medications through an implanted pump (see below). Taking extra care when moving from a chair or bed can also help keep triggers from occurring. Avoiding temperature extremes, especially cold temperatures, may also decrease spasticity. Bowel problems can be avoided by eating a high fiber diet and drinking plenty of water.

Physical Treatments

The following treatments will help to maintain flexibility and therefore reduce spasticity and the risk for permanent joint contracture:

- Regular stretching (range-of-motion) exercises will help maintain flexibility and temporarily reduce muscle tightness in mild to moderate spasticity.

- Standing with support, often with the help of braces, will help stretch muscles.

- Splints, braces, or temporary casts that are adjusted as range of motion improves provide continuous muscle stretching that helps to maintain flexibility.

- Careful use of cold packs or stretching and exercise in a pool may help.

It is important to get the advice of a physician or therapist on what physical treatments are correct and safe.

Oral Medication

Medications may help control spasticity but may have side effects and are probably most useful when you have spasticity in several parts of your body. Common side effects, such as sleepiness, may be more of a problem after a brain injury. You should discuss the benefits and side effects of these medications with a physician. Appropriate medications may include:

- Baclofen (Lioresal®)

- Dantrolene (Dantrium®)

- Tizanidine (Zanaflex®)

- Benzodiazepines such as diazepam (Valium®) or clonazepam (Klonopin®)

- Gabapentin (Neurontin®)

- Cannabis (a lack of standardized products in the United States makes recommendations difficult; there is minimal evidence in TBI to guide risk-benefit decisions. Cannabis remains illegal in certain states.)

Focal Interventions

Sometimes a person may have side effects from oral medication or may only have spasticity in a few muscles. For those types of spasticity, anesthetic medications, alcohol, phenol, or botulinum toxin (Botox®, Dysport®, Xeomin®, Myobloc®) can be injected into the affected muscles or nerves (usually in the arms and legs) to reduce unwanted hyperactivity and to control spasticity. Cryotherapy is another technique that can decrease spasticity in a few selected muscles. The most common side effects of these procedures are pain related to the injections themselves or weakness in the targeted or nearby muscles. The benefits of the injections are temporary (usually several months), so they may need to be repeated several times a year. These injections require regular stretching and other therapies to be most effective. Injections can be used safely in combination with other spasticity management interventions.

Intrathecal Baclofen (ITB) Pump

Intrathecal baclofen pumps are small hockey-puck sized devices that release tiny amounts of baclofen into the space around the spinal cord. Baclofen is the most commonly used intrathecal medication. Intrathecal baclofen pumps can be especially helpful after a TBI when the spasticity is severe and widespread. Surgery is performed to implant a small battery-powered pump, usually in the patient’s abdomen. Intrathecal baclofen can be used along with other spasticity treatments. Like other treatments, this pump can reduce the frequency and intensity of spasms. It has the advantage of maximizing the beneficial effects of baclofen with fewer side effects than taking baclofen (or other spasticity medications) by mouth. Although rare, there can be serious complications associated with intrathecal baclofen and the pump needs to be replaced every 5–7 years. It is important to discuss the risks with your physician and carefully follow instructions.

Refrences

Bell, K., & DiTommaso, C. (2016). Spasticity and traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(1), 179–180.

Wong, B. S., Iaccarino, M., & Zafonte, R. D. (2021). Spasticity in traumatic brain injury. In F. S. Zollman, (Ed.), Manual of traumatic brain injury: Assessment and management. Springer Publishing Company.

Nalla, S., & Watanabe, T. (2024) Pharmacological treatments. In M. Verduzco-Gutierrez & N. C. Ketchum (Eds.), Handbook of spasticity. Springer Publishing Co, LLC.

Chokshi, K. & Flanagan, S. (2021) Spasticity. PM&R KnowledgeNow. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. https://now.aapmr.org/spasticity/

Authorship

Spasticity after Traumatic Brain Injury was originally developed by Kathleen Bell, MD, and Craig DiTommaso, MD, in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC) in 2015. It was reviewed and updated by Thomas Watanabe, MD, Kathleen Bell, MD, and Craig DiTommaso, MD, in collaboration with the MSKTC in 2024.

Source: The content in this factsheet is based on research and/or professional consensus. This content has been reviewed and approved by experts from the Traumatic Brain Injury Model System (TBIMS) centers, funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, as well as experts from the Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRCs), with funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The content of the factsheet has also been reviewed by individuals with TBI and/or their family members.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this factsheet were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0082) and were updated under an NIDILRR grant (90DPKT0009). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this factsheet do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Recommended citation: Watanabe, T., Bell, K., and DiTommaso, C. (2024). Spasticity and Traumatic Brain Injury. Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/spasticity

Copyright © 2024 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution. Prior permission must be obtained for inclusion in fee-based materials.