What you need to know?

- Your ability to control urine release may be limited because of injury. You may not be able to stop urine from flowing out of your body, or you may not be able to release urine from your body.

- The inability to control the release of urine is called “urinary incontinence” (pronounced in-KAHN-ten-ens).

- The inability to release urine is called “urinary retention.”

- Surgery can sometimes be used to help manage these problems if nonsurgical bladder management approaches do not work. Surgeries that use a part of your intestines will be discussed.

- All surgery comes with risks of bleeding, serious infection, and other side effects.

- More than one surgery may be needed to manage your bladder function.

- Surgery using the intestine to enlarge the bladder or as a substitute for the bladder is very rarely used in adults with SCI. It is more commonly used in children with spina bifida who have a very damaged bladder or in adults who have their bladders removed because of bladder cancer.

- Because surgery using the intestine is used so rarely in adults with SCI, we do not have enough information to discuss risks, benefits, alternatives, and the specific impact on lifestyle in adults with SCI. Therefore, it is very important that you speak with a surgeon who is very experienced in this type of surgery and a rehab doctor to discuss how surgery may help in your specific case.

- To learn about the problems caused by your injury and the strategies used to help you manage bladder problems (see MSKTC factsheet entitled Bladder Management Options Following Spinal Cord Injury).

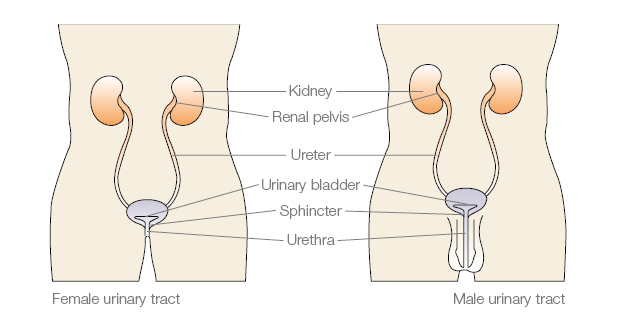

Understanding your urinary tract

Waste from your body is removed from your blood stream by your kidneys and becomes urine. Normally, urine passes down the ureters into your bladder (a small pouch that holds your urine located in the lower middle part of your abdomen below your beltline). A sphincter (pronounced SFINK-ter) made of muscle circles the opening of your bladder, where urine flows out of your bladder. The sphincter acts like a valve that opens and closes to control when the urine comes out of your body. When you urinate, your bladder squeezes and your sphincter relaxes. Urine passes from the bladder through the urethra (pronounced yur-EETH-rah) and out of your body. In women, the urethral opening is right above the vagina. In men, the urethral opening is at the tip of the penis. Surgery may involve any of these parts of your urinary tract as well as your intestines or your stomach.

Why do I need surgery that uses part of my intestine?

Sometimes, your injury or other health issues may limit your ability to use traditional bladder management methods, or the traditional methods are not working as well as they should. The goal of surgery, like other bladder management strategies, is to enable you to remove urine from your body and keep your kidneys healthy and maintain a life style that is best for you. Some of the reasons you might need surgery are:

- You would like to perform intermittent catheterization but this is not practical because you have a very small overactive bladder (a bladder that squeezes with only a small amount of urine in the bladder) despite medications.

- Your bladder has lost its ability to stretch and therefore develops a high pressure when it fills up with urine, causing back pressure and damage to your kidneys despite medications.

- You have a problem that cannot be treated with medications, such as an over-stretched or damaged urethra, which is causing constant urinary leakage.

Will surgery cure my bladder problems?

Surgery cannot make your bladder work normally, but it can:

- Help you be able to use a bladder management strategy such as intermittent catheterization.

- Create new ways for you to release urine from your body.

What are some surgical procedures that use part of my intestine?

There are a number of surgical procedures and variations involving the use of your intestine to help with your bladder problems. The type of surgical procedure that may help you depends on the problem you are having with your bladder and what type of bladder management you would like to have. Below are two common types of surgical procedures.

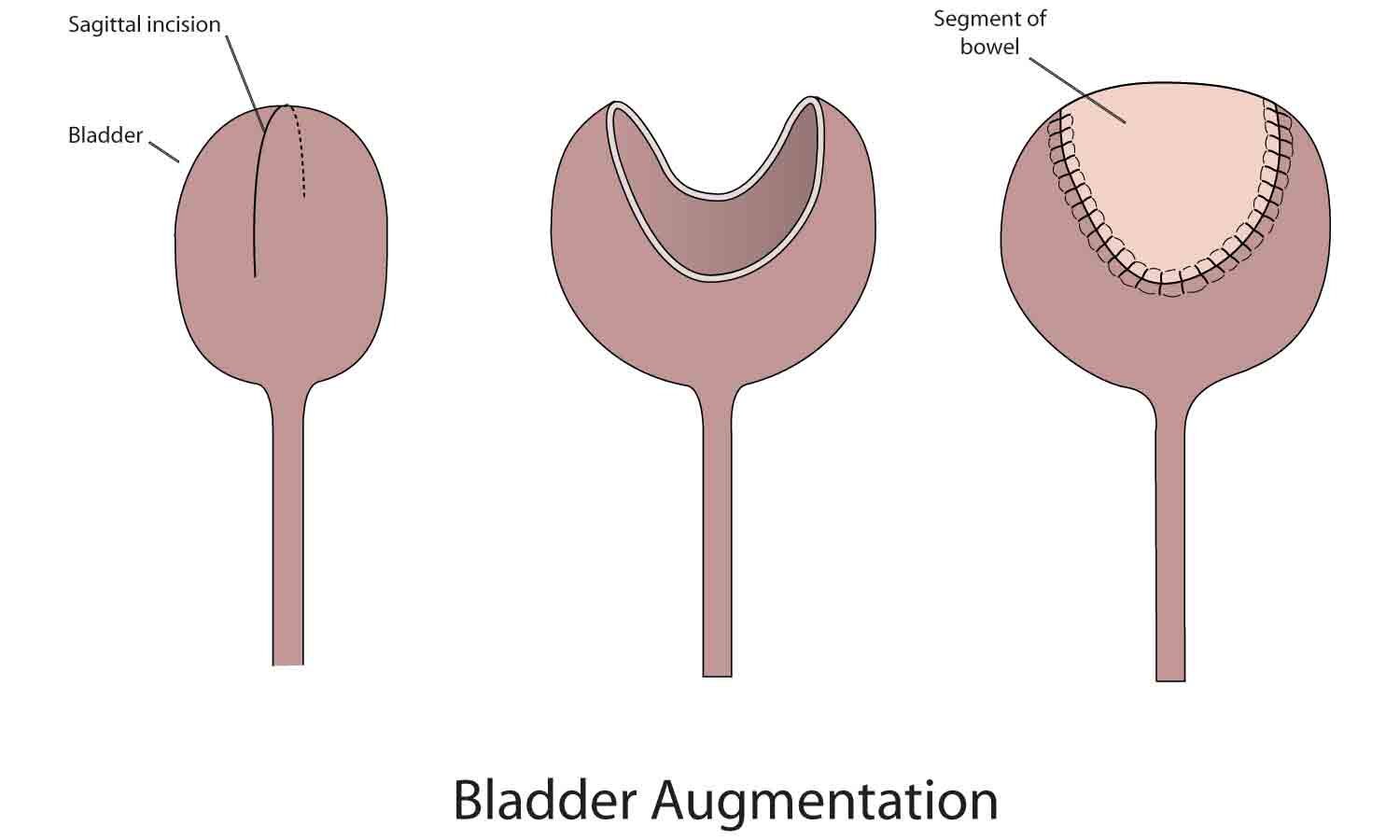

Bladder Augmentation Surgery

Bladder augmentation (pronounced aug-men-TAY-shun) surgery is for people who are having kidney damage because they have a small bladder with forceful squeezing that causes back pressure to the kidneys. It is also helpful for people who want to perform intermittent catheterization but have a small, overactive bladder despite medications. You should not have this surgery if you are unable or unwilling to perform intermittent catheterization or if you have problems with your bowels such as inflammatory bowel disease. The surgery increases your bladder size so that it has less forceful squeezes (more relaxed), enabling it to hold more urine at one time. It does not improve the way your bladder functions. Having a larger, more relaxed bladder makes it easier for urine to drain from your kidneys into your bladder and more practical to perform intermittent catheterization (for a description of intermittent catheterization, see MSKTC factsheet entitled Bladder Management Options Following Spinal Cord Injury http://www.msktc.org/sci/factsheets/bladderhealth).

During the surgery:

A surgeon removes a small part of your intestine and then sews the piece onto your bladder, much like sewing the top of a clamshell (intestine) onto the bottom of a clamshell (bladder) to make the bladder larger. If you have a weak sphincter, you may start to leak urine from your urethra. In this case you may need treatment of your sphincter to make it stronger. You and your doctor may consider additional surgical treatment to tighten your sphincter or use a urinary diversion as discussed below.

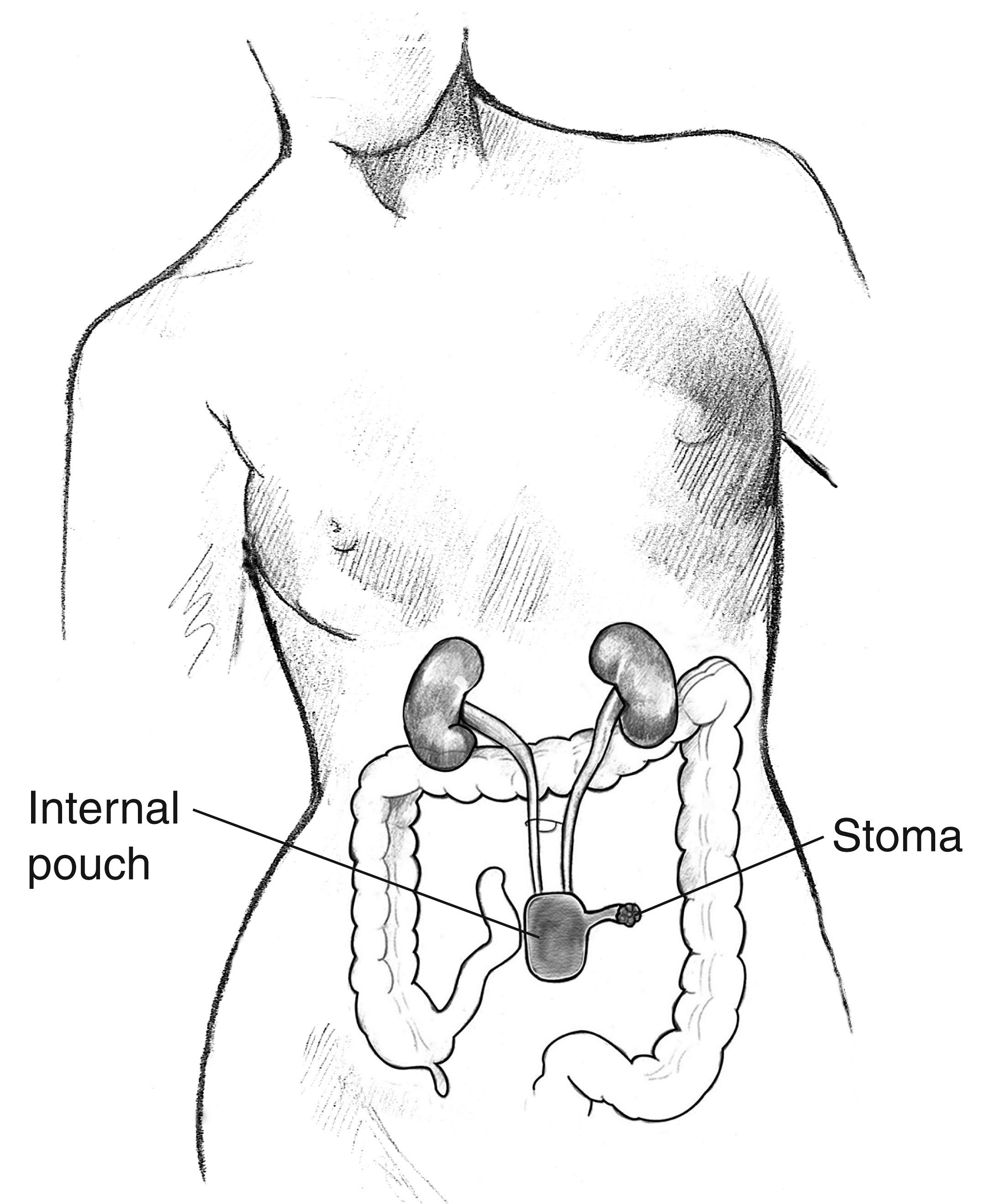

Urinary Diversion

Urinary diversion redirects the urine flow from your bladder to a pouch of intestine that has been made to hold your urine. This surgery is for people who have a very small, damaged bladder that cannot be improved with a bladder augmentation; a bladder that has to be removed for some reason such as cancer; or a very damaged urethra that makes it difficult to pass a catheter into your bladder. In this surgery:

- A surgeon creates an artificial bladder using parts of your stomach or intestine.

- The surgeon then sews your ureters into the new pouch.

- Another piece of intestine is used to make a tube from the pouch to an opening on your abdomen (this opening is called a “stoma” (pronounced STOH-mah).

- Sometimes the pouch can be sewn directly onto your urethra, so you can drain your bladder through your urethra rather than a bag or catheter.

Incontinent Urinary Diversion

This form of urinary diversion is called “incontinent” because there is nothing holding the urine in the new bladder. Urine drains out of the opening in your abdomen (stoma) as soon as it is made. A bag outside of your body is attached to the stoma to collect this urine. You can empty the bag whenever it is full.

Continent Urinary Diversion

This form of urinary diversion is called “continent” because the stoma is made with a small fold that keeps the urine from draining out on its own. The urine is held in the new bladder and removed by passing a catheter down through the stoma into the new bladder.

What are the risks of surgery?

All surgery comes with risks. “Risk” means that these problems could happen; it does not mean that they will happen. Talk with your surgeon or doctor about your overall health and what may be a higher risk for you. There are two types of risks, short-term risks that occur right after surgery and long-term risks (late complications) that can occur later on. Long-term complications take time to develop and may occur several weeks, months, or even years after your surgery.

Some of the more common possible short-term surgical risks include:

- You could have an allergic reaction to or other problems with the anesthesia (pronounced an-es-THEE-zha), the medicine used to put you to sleep during surgery.

- You could develop pneumonia after surgery.

- The wound where the surgery is performed could become infected.

- Your intestines could take a long time to “wake up” after surgery, causing discomfort, vomiting, and constipation.

- You could develop a deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

- You could have a urine leak or blockage or other problem from the intestine where you had your surgery, which could require another operation.

Some of the more common possible late risks/complications from bladder augmentation or urinary diversion surgery include:

- Increased risk of kidney or bladder stones.

- A tear/rupture of your new intestine pouch due to over-stretching (rare).

- Loose stools or diarrhea, depending on the part and amount of your intestine that is removed.

- Increased risk of cancer at the area around the bladder and intestine (rare).

- Bowel obstruction (blockage) caused by part of your intestine getting caught in some of the scar tissue from your surgery. This is often a surgical emergency requiring surgery to correct the blockage to prevent your intestine from rupturing and causing you to become extremely sick.

- Mucus in the urine because the piece of intestine attached to the bladder may create a lot of mucus. Sometimes this can clog the catheter you are using to drain your bladder or make it difficult to know for sure if you might have a bladder infection.

- There are also specific metabolic changes and other possible complications, depending on which part of your intestine (or your stomach) is used. Your surgeon will be able to tell you more about these possible risks.

Some of the more common possible late complications from urinary diversions (only) include:

- Scar tissue around the tube from the kidney, which squeezes the tube partially shut.

- Narrowing of the skin around the stoma can make it difficult for urine to drain out of the intestinal pouch or pass a catheter down into the intestine pouch to drain the urine.

- Parastomal hernia. The piece of intestine that goes from the pouch up to the skin starts to push up and around the opening of the skin (stoma).

For more details on bladder management including surgical management see: Bladder management for adults with spinal cord injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care providers. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29(5):527-73.

Ask your doctor about your level of risk for any of these complications, and what can be done if any of them occur.

Authorship

Surgical Alternatives for Bladder Management Following SCI was developed by Todd A. Linsenmeyer, M.D., and Steven Kirshblum, M.D., in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center.

Source: Our health information content is based on research evidence and/or professional consensus and has been reviewed and approved by an editorial team of experts from the Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this fact sheet were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0012-01-00). The contents of this fact sheet do not necessarily represent the policy of Department of Health and Human Services, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Copyright © 2015 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution. Prior permission must be obtained for inclusion in fee-based materials.