What does the respiratory system do?

Your respiratory system (or pulmonary system) is responsible for breathing. This system enables you to inhale oxygen into your blood and exhale carbon dioxide. Your body needs the oxygen to survive, and carbon dioxide must be removed to avoid the build-up of acid in your body.

How does the respiratory system work?

You normally breathe without thinking about it, but your brain is carefully coordinating this activity. Your brain sends signals down your spinal cord to the phrenic nerves which start at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th cervical spinal levels to contract the diaphragm.

- You can learn more about spinal nerve function in the fact sheet,“Understanding Spinal Cord Injury, Part 1 – The Body Before and After Injury.”

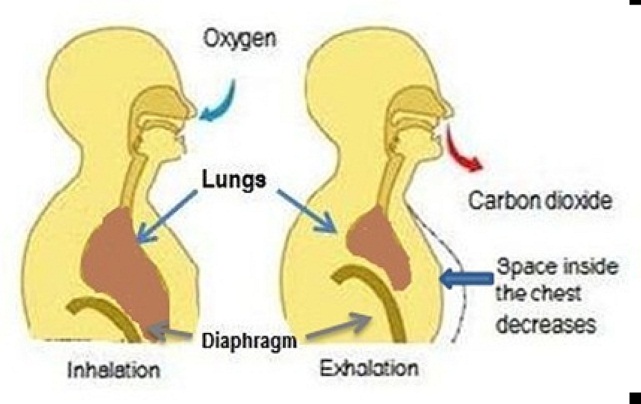

Your diaphragm is the dome-shape muscle located under each lung (at the bottom of your chest) and is the primary muscle used for inhaling. The diaphragm moves down as it contracts. Your lungs, rib cage and abdomen (belly) expand as air is drawn into (inhaling) your lungs through your nose and mouth. Air travels through the main airway (the trachea) and smaller airways (a series of tubes) that lead to the air sacs. Air sacs in your lungs transfer oxygen from the air to your blood. Your diaphragm moves up to where it started as it relaxes after inhalation. Your lungs, rib cage and abdomen (belly) get smaller as the muscles of inhalation relax, pushing carbon dioxide out (exhaling) through your nose and mouth.

You normally need more muscle strength, or force, to help with breathing when you exercise or cough. To provide this added assistance, particularly to help with exhaling forcefully during a cough, your brain sends signals down your spinal cord and out through the nerves coming from the thoracic portion of the spinal cord to direct your abdominal muscles (over your belly) and intercostal muscles (between the ribs).

- Coughing is important because you produce small amounts of mucus in your lungs every day.Coughing helps to remove the mucus and prevent mucus build-up that can block the airways leading to the air sacs in your lungs that absorb the oxygen from the air. When you cough, the muscles responsible for most of the force are the abdominal muscles.

How does spinal cord injury impact the respiratory system?

Signals sent from your brain can no longer pass beyond the damage to the spinal cord, so your brain can no longer control the muscles that you would normally use for inhaling and exhaling. The extent of your muscle control loss depends on your level of injury and if there is complete or incomplete spinal cord damage.

If you have a complete high cervical injury that involves the spinal cord at or above the cervical 3rd, 4th, and 5th spinal nerves, you may have a loss of or weakness in diaphragm function depending on the extent of damage. You may even need a tracheostomy (an opening through the neck into the trachea, the main airway to help a person breathe) or ventilator (a machine that helps a person breathe by pushing air into the lungs). With a complete lower cervical injury that does not involve the cervical 3rd, 4th, and 5th spinal nerves, diaphragm function remains and usually a ventilator is not needed. In high and low complete cervical injury, you also will have a loss of control of your abdominal muscles (over your belly) and intercostal muscles (between the ribs). In incomplete cervical injuries, the degree of diaphragm weakness or loss of other muscle control depends on the extent of damage. If you have a thoracic level of injury (see image), you can lose some or all control of your abdominal muscles (over your belly) and intercostal muscles (between the ribs). The amount of loss depends on the location and extent of spinal cord damage. If you have only lumbar or sacral injury levels then your abdominal and intercostal muscles are not affected.

If you require a ventilator to breathe due to loss of diaphragm function, a pacing system to stimulate the diaphragm may be an option.

How does loss of muscle function affect my health?

If you have a loss of respiratory muscle control, the muscles that are still functioning have to work harder to get oxygen into your blood and to get rid of the carbon dioxide. You may also have trouble coughing with enough force to get rid of mucus in your lungs. This puts you at an increased risk for respiratory health problems.

- Both a higher injury level and whether a person has complete or incomplete injury contribute to the risk of respiratory problems.

- Persons with a higher and more complete injury (for example, complete cervical) are at higher risk for respiratory problems than persons with a lower and incomplete injury.

What health problems are common?

Bronchitis is an infection in the tubes that lead to the air sacs in the lungs, and pneumonia is an infection in the air sacs. These infections are very serious health problems because extra mucus is produced. Mucus will build up if the ability to cough is reduced due to muscle weakness or paralysis. The buildup of mucus can result in atelectasis (at-uh-LEK-tuh-sis), which is a collapse of all or a portion of the lung.

Although people with cervical or thoracic injury are at highest risk for having complications, such as atelectasis with these infections, those with the highest risk are those who:

- smoke

- have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- have a tracheostomy

- use a ventilator

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is another common problem. OSA occurs when a loss of muscle tone during sleep in the tongue, soft palate or other soft tissues of the throat allows the airway to collapse and obstructs the flow of air when you try to breathe in. This typically causes a drop in blood oxygen level and a rise in blood carbon dioxide level. The brain responds with a brief arousal to “jump-start” breathing. This disruption of sleep repeats throughout the night, but most people are not aware of it, because it does not cause them to fully wake up. Even though it may not wake you up, the sleep disruption can make you sleepy during the day, no matter how long you sleep at night. OSA is also associated with a number of medical problems such as:

- depression

- diabetes

- heart attacks, heart failure, and irregular heartbeat

- high blood pressure

- stroke

- death

Anyone can have OSA, but the risk is greater for people who:

- snore

- are male (the risk of OSA is also higher in post-menopausal than in pre-menopausal women)

- are overweight or obese

- drink alcohol

- take muscle relaxant medication

- have a small jaw, enlarged tonsils, or difficulty breathing through the nose

What can I do for my respiratory health?

Prevention - Your first defense is to do whatever you can to prevent respiratory health problems. Here is a checklist.

- Do not smoke and stay away from secondhand smoke! Exposure to tobacco smoke is the worst thing you can do for your health. Smoking causes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and lung cancer, and exposure to cigarette smoke diminishes your health in many, many ways. COPD can cause the body to produce extra mucus and also causes a reduction in lung function in addition to the reduction in lung function attributable to the muscle weakness and paralysis that accompanies spinal cord injury. Plus, exposure to smoke can make worse many health problems you develop.

- Avoid the buildup of secretions in the lungs. If you have difficulty coughing and clearing secretions, a cough assist machine can be helpful in keeping your lungs clear. If you have a tracheostomy with or without a ventilator, you can also use a suction tube to keep your lungs clear. An attendant or family member can also be trained to manually assist with coughing.

- Stay hydrated. Drink plenty of water, especially if you have an infection, unless your doctor tells you something different.

- Keep a healthy weight! People who are overweight or obese typically have more problems with their lungs. They also tend to get obstructive sleep apnea. Ask your health care providers to recommend a diet if you are overweight and an exercise program to help maintain fitness. There is evidence from non-SCI populations that maintaining a high level of activity and taking part in rehabilitation programs that typically include both an aerobic and strength training component prevent future health problems. Persons with SCI who take part in an exercise program or in a sport also report a higher quality of life.

- Stay away from people who may have a cold or flu.

- Get a flu shot every year. This shot will help keep you from getting the flu but does not cause the flu.

- Get a pneumonia shot. Pneumonia and other pulmonary infections are among the most common causes of death following SCI, but the shot can help keep you from getting a common type of bacterial pneumonia. In persons age 65 or older, revaccination with the same shot you received before 65 is suggested. Furthermore, an additional pneumonia vaccine has been developed for persons age 65 or older that is directed at other types of this common bacteria. You should ask your health care provider about the timing of shots based on current guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Watch – Even with your best efforts to prevent respiratory health problems, they can still develop. The sooner you can identify any problems, the better your chance of treating them and getting better.

Signs and symptoms of a lung infection (bronchitis and pneumonia) are not always easy to identify. Mild signs and symptoms might first seem like those of a cold or flu, but they can last longer and get worse over time.

Some signs and symptoms of infection may include:

- Fever and chills

- Cough or feeling the need to cough (coughing may produce thick, sticky mucus that might be clear, white, yellowish-gray or green in color, depending on the type of illness)

- Tightness in the chest

- Shortness of breath

Signs and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea may also be mild at first and get worse over time. In fact, you might wake and fall back asleep many times throughout the night without realizing it. However, you can watch for some common signs that suggest you might have sleep apnea:

- Other people tell you that you stop breathing at night

- Loud snoring

- Restless sleep (especially if you awaken choking or gasping for air)

- Waking up with a sore and/or dry throat

- Waking with a headache

- Daytime fatigue, sleepiness, or not feeling rested after sleeping

Visit your Healthcare Provider – You should see your healthcare provider every year for a check-up to check for the health problems common to someone your age and with your type of injury. Persons with lung disease, such as COPD or asthma may need to see a provider more often.

- ALWAYS go see your provider if you have signs of a respiratory infection. It is important to be aggressive and avoid waiting until a mild problem becomes a much larger health problem.

- ALWAYS go see your provider if you think you have sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is a serious condition. Your provider can set you up to get a sleep study and find a treatment option that works for you.

- Ask your provider if you should get a lung function test to see how well your lungs function. This is especially important if you have ever smoked, have COPD, or have asthma. If you have problems breathing, you may need medication that opens the airways to help the lungs work, helps you breathe easier, and makes it easier to do your day-to-day activities.

Authorship

Respiratory Health and Spinal Cord Injury was developed by Eric Garshick, MD, MOH, Phil Klebine, MA, Daniel J. Gottlieb, MD, MPH, and Anthony Chiodo, MD in collaboration with the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center. Dr. Garshick and Dr. Gottlieb are members of the Pulmonary, Allergy, Sleep, and Critical Care Medicine Section, VA Boston Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs, Boston, MA.

Source: Our health information content is based on research evidence and/or professional consensus and has been reviewed and approved by an editorial team of experts from the Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems.

Disclaimer: This information is not meant to replace the advice of a medical professional. You should consult your health care provider regarding specific medical concerns or treatment. The contents of this fact sheet were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0012-01-00). The contents of this fact sheet do not necessarily represent the policy of Department of Health and Human Services, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Copyright © 2015 Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC). May be reproduced and distributed freely with appropriate attribution.